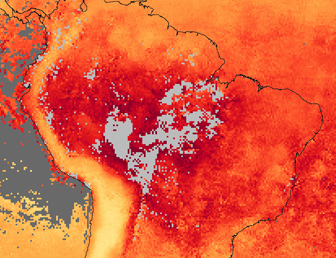

Throughout September 2007, intense fires burned across South America, and the skies were frequently thick with smoke. Carbon monoxide is one of several gases released by burning vegetation. Because of its relatively long lifetime in the atmosphere, carbon monoxide is a good tracer of smoke-related pollution. This image of the continent shows satellite observations of carbon monoxide for September 2007, measured by the measurements of Pollution in the Troposphere (MOPITT) sensor on NASA's Terra satellite. The image shows the column density of carbon monoxide, which is the number of molecules of carbon monoxide in a 1-square-centimeter column of the atmosphere. The image shows how the fires have increased carbon monoxide levels over the Amazon Basin (dark red) in the heart of the continent.... Places where MOPITT could not collect enough data to make an estimate of carbon monoxide (probably due to clouds) are gray. Some smoke apparently spilled westward over the equatorial Pacific Ocean, but a larger amount spread eastward over the Atlantic Ocean. NASA image created by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory, using data provided by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and the University of Toronto MOPITT Teams. Caption courtesy of NASA's Earth Observatory. |

"I have never seen fires this bad," he told mongabay.com. "The fires are even worse than in 1998´s El Niño event."

NASA satellite images released at the end of September confirm widespread burning in the Amazon state of Mato Grosso.

"On September 29, 2007, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite captured this image of the southern Amazon, showing widespread fires (locations marked in red) in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil," reported NASA's Earth Observatory. "Fires are also clustered along the sides of two major roads that penetrate the heart of the Amazon: the Trans-Amazon highway in the state of Amazonas, and the unpaved portion of the BR-163 Highway in the state of Pará. (The paved portion extends through Mato Grosso.) Fires surround the Xingu Indigenous Park and line the banks of the river that meanders north through the park's center."

Carter adds that the smoke from fires has made it difficult to navigate by plane.

"Three weeks ago I tried to land at the Kamayura Indian village and upon flying 300 feet over the village, was not able to land because I could not see it do to the smoke," he said. "A huge area of the Xingu National Park was on fire, truly sickening as it is a sign of things to come."

Fire in the Amazon

Fires in the Amazon are usually the product of human activity. Generally, fires are set to clear land for agriculture, though in dry years fires may escape agricultural areas and burn widely through forest area. For example, during the record drought of 2005-2006, thousands of square kilometers of land burned for months, releasing more than 100 million metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere.

Scientists are concerned that continued burning in the Amazon could cause the world's largest rainforest to tip towards large-scale ecosystem change, whereby tropical forest is replaced by savanna.

"The threat of a 'permanent El Niño' is therefore to be taken very seriously," said Dr. Philip M. Fearnside of the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) in an interview with mongabay.com last year. "Disintegration of the Amazon forest, with release of the carbon stocks in the biomass and soil, would be a significant factor in pushing us into a runaway greenhouse."

"It's not out of the question to think that half of the basin will be either cleared or severely impoverished just 20 years from now," added Dr. Daniel Nepstad, head of the Woods Hole Research Center's Amazon program. "The nightmare scenario is one where we have a 2005-like year that extended for a couple years, coupled with a high deforestation where we get huge areas of burning, which would produce smoke that would further reduce rainfall, worsening the cycle. A situation like this is very possible. While some climate modelers point to the end of the century for such a scenario, our own field evidence coupled with aggregated modeling suggests there could be such a dieback within two decades."

NASA image courtesy the MODIS Rapid Response Team, Goddard Space Flight Center |