Should the U.S. Build Its Next Coal Plants Underground?

Momentum is growing worldwide to look closely at the idea, a 150-year-old technique of igniting seams of coal deep under the ground to produce electrical power or chemicals. It's a proven technology: Joseph Stalin launched the first national research program into the idea in 1928 and the Soviets used it for 40 years to produce power. Since then, cheap natural gas and shallow, easy-to-mine coal burned in traditional power plants have prevented the technique from taking off.

But gasifying coal underground is now a hot topic among power companies and scientists, with at least 10 pilot projects around the world planned or underway. The cost benefits and climate advantages are among the reasons that five countries run national research programs on the technique; is the United States falling behind on the next big fossil fuel technology?

Yes, says the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force, a well-respected public health and environment advocacy group, in a report issued last week.

"The enormous potential of underground coal gasification to meet rising energy demand in a CO2-constrained world warrants a high priority effort by the United States government to speed commercialization," the Task Force study said.

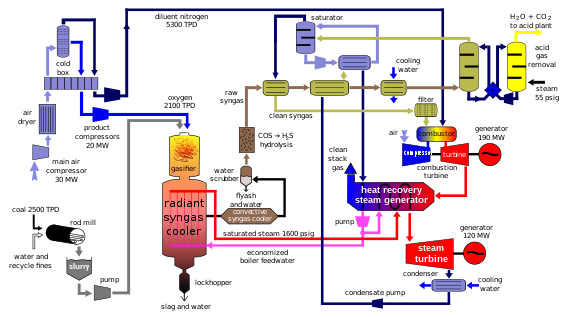

The advantages of the techniques are myriad, says the Task Force, starting with the fact that it's a cleaner version of "clean coal" than other techniques:

So if underground coal gasification is so great, why are commercial projects exploiting the method so few and far in between? Up till now, the reason is the availability of cheap energy using other means, author Julio Friedmann of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California tells ScienceInsider. During the late '70s energy crisis, the technology got several demonstrations in the United States, but the coal industry stuck with the methods it liked, especially because they owned rights for coal close to the surface. Plentiful and cheap natural gas was a further disincentive.[D]uring gasification, roughly half of the sulfur, mercury, arsenic, tar, ash, and particulates from the used coal remain in the subsurface, and any sulfur or metals that reach the surface arrive in a chemically reduced state, making them relatively simple to remove.

Now though, with natural gas prices rising and climate a central concern, Australia, Canada, China, New Zealand, and South Africa all have government-funded R&D projects in this area. "China has minted 100 Ph.D.'s in this area," says John Thompson, director of the Task Force's project on coal transformation. "We are losing."

For its part, the report suggests DOE spend more than $100 million over the next 4 years on science, development, and demonstration efforts to try to catch up.